Introduction

Citizenfour is about NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s actions as well as the collective work of reporters, and whistleblowers Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald, Ewen MacAskill, Jeremy Scahill and William Binney.

Laura Poitras produced My Country, My Country in 2006. In that film she explained life for Iraqis under American occupation. In 2010, she produced The Oath, which covered two Yemenis’ relation to Gitmo and the War on Terror. Poitras also produced The Program, which discusses the domestic surveillance enterprise in Bluffdale, Utah. As a result of this body of work, Poitras undergoes monitoring by the United States Government, and is harassed routinely by border patrol agents.

Laura Poitras is not shown in the film. She compares this to never seeing a writer in a book. For her, the work is about what is unfolding in front of her camera. She is the film’s narrator. Poitras obtained some 20 hours of Edward Snowden footage to make the film. The film is done in the style of “direct cinema,” originated by Jean Rouch. Citizenfour shows what happened, as it happened.

Spoiler Alert: If you don’t want to know what happens in the movie, skip to “Conclusion.”

Citizen Four’s Anonymous Emails to Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald

In the film’s opening scene, Poitras’s voice can be heard as a car proceeds through a very dark tunnel showing only a light trail above. Citizen Four’s initial emails are read by Poitras to the audience. Poitras reads:

“Laura, at this stage I can offer nothing more than my word. I am a senior government employee in the intelligence community. I hope you understand that contacting you is extremely high risk … From now, know that every border you cross, every purchase you make, every call you dial, every cell phone tower you pass, friend you keep, … site you visit … subject line you type … is in the hands of a system whose reach is unlimited but whose safeguards are not. … In the end if you publish the source material, I will likely be immediately implicated. … I ask only that you ensure this information makes it home to the American public. … Thank you, and be careful. Citizen Four.”

The film’s portrayal of the transfer of important digital files

Snowden calls himself Citizen Four because he believes he is not the first person within the NSA to find the actions of the United States Government deplorable. He also insists that the story should not be about him but about his actions and the potential actions of others. Citizen Four contacts Poitras because he is aware of her involvement in reporting and film making, but most importantly, he knows how she is being victimized by the NSA’s far-reaching system at airports.

The film goes on to discuss Presidential Policy Directive 20, a 2012 strategy implemented by President Obama to broaden, enlarge and strengthen the existing Bush-era national security procedures.The film successfully reveals the erosion of judicial oversight when it comes to national security in the United States, especially in relation to matters where no national security is at stake. It suggests that the real goal of security is for the actions of power and privilege to be insulated from the public.

In a case involving Mark Stein and AT&T, a judge on close circuit television remarks to the attorney, “What role do Justices have, would you like us to just go away?”

Tech activist Jacob Appelbaum is seen at a conference describing the concept of “linkability.” Linkability is the concept of tracing citizens in order to know where they are at all times based on information and technology. To Appelbaum, this is very alarming.

Glenn Greenwald’s first Citizen Four-related story is on Verizon and is headlined worldwide. It is based on Citizen Four’s email:

“Publicly, we complain that things are going dark, but in fact, their accesses are improving. The truth is that the NSA in its history has never collected more than it does now. I know the location of most domestic interception points, and that the largest telecommunication companies in the US are betraying the trust of their customers, which I can prove.”

The Hong Kong Revelations

Greenwald and Poitras organize to meet with Citizen Four in the hotel lobby in Hong Kong. Snowden explains that he will be working on a Rubik’s cube. That is how they are to identify him:

“On timing, regarding meeting up in Hong Kong, the first rendezvous attempt will be at 10 A.M. local time on Monday. We will meet in the hallway outside of the restaurant in the Mira Hotel. I will be working on a Rubik’s cube so that you can identify me. Approach me and ask if I know the hours of the restaurant. I’ll respond by stating that I’m not sure and suggest you try the lounge instead. I’ll offer to show you where it is, and at that point we’re good. You simply need to follow naturally.”

In the hotel room in Hong Kong are Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras and Ewen MacAskill. They discuss the content of some of Citizen Four’s documents and Snowden lets them know his name, and how the NSA was spinning out of control. Snowden felt that NSA policy construction was reaching a point where it could never be meaningfully opposed by citizens.

Snowden reveals in the film that he was born in North Carolina and he goes by Ed. He comes from a military family in the section known as Elizabeth City in Pasquotank County. He then moved to Fort Meade, Maryland because his father worked near Washington DC. To this day, in DC, taxi drivers have stories about how they used to drive Snowden around the DMV area in the early 2000s. They comment that he looked the exact same way, and they collectively agree that Snowden was decent to drivers and tipped well to union members specifically.

The famous Honk Kong interview with Snowden

Snowden added that some people involved in security state surveillance are extremely bright while also describing some as completely mediocre. In other words, the tools and capability for people to watch everyone were no longer specialized; there was a generic function and incredible possibilities for anybody to be watched at any time, routinely within the NSA. There is an expectation to be under the NSA gaze.

Snowden additionally commented on how at NSA you could log-on and watch a drone strike from any desk. The expectation was that all things were to be watched. Furthermore, he informed the reporters in his hotel room that all of the information coming in to be investigated was entering in real time.It was not being stored to be investigated at a later date.

Snowden then describes to the reporters GCHQ and its program called Tempora. GCHQ is The Government Communications Headquarters in Britain. This intelligence gathering facility supplies signals intelligence to the British military and government. He describes the meaning of a “full take” enterprise. This is a full sweeping collecting of data without any discrimination. Snowden is alarmed that there is collusion with a foreign government to network domestic watching. In other words, Snowden reveals that what happens in the GCHQ is illegal in the United States but the UK, according to one of Snowden’s emails, “let us query it all day long.”

Snowden it seems has so much knowledge of NSA capability that to the average citizen his concerns may appear to border on paranoia. In the hotel Snowden, explained to the reporters that the phone needed to be unplugged since there are devices inside phone receivers even when hung up. He knows this because he has been a part of efforts to make them. Snowden also has a ritual in the hotel room – he would always cover his head when typing in his password. This is someone fully aware of the consequences, and he knew the inevitability of having “a target on his back.”

Snowden lets the reporters know that at NSA, 1 billion telephones and internet sites could be watched simultaneously and that the Department of Defense has 20 sites set up working to equal 20 billion people being watched at once.

The Tempora story is reported by Glenn Greenwald in The Guardian without mention of Edward Snowden. The reaction to the leaks was fast and furious. Here, the as-it-happened-style of the film is at its best. Snowden is seen in the film watching the story break before he is known to the world. Greenwald was a guest on CNN as he discussed the danger of neglecting court orders to conduct indiscriminate and sweeping collections of people’s personal data. He talked about how perilous it is for the government to eliminate the warrant requirement.

Journalists of the Hong Kong interview

After Greenwald appeared on CNN, Snowden received a call in his hotel room that the NSA Human Resources director had shown up at his house. They just entered and broke in. No one knew where Snowden was, since he routinely disappeared for work for various projects and trips. Lindsay Mills, Snowden’s partner, explained that the rent checks were not being wired through properly and that the street where Snowden lived was lined with construction vehicles. This may have propelled him to go public sooner since it provided a crystal clear example that his identification was soon to come. Greenwald urges him to consider coming out and Snowden agrees. He does emphasize however, his worry that the story will become about him instead of an issue of public concern.

The Aftermath of Snowden Coming Out as the Leaker and Whistleblower

On June 10, 2013, Snowden had agreed to go public by allowing Greenwald to expose his identity. Snowden explained how he was an infrastructure analyst for the NSA with top secret classified information. When the story broke that Snowden was the leaker, his name and image were suddenly visible worldwide and the film illustrates the impact on Snowden of becoming an icon instantaneously. Producer Laura Poitras asked if he was okay. Seconds later, the phone rings and Snowden answers – it is the Wall Street Journal which had tracked him down in the hotel in Hong Kong just moments after the story broke. This is one of the more fascinating scenes in this cinema verité.

Moments after that call, other calls start to pour in and Snowden is in need of a Hong Kong human rights attorney to get him out of the hotel safely. In Poitras’s room he discusses with the human rights attorney asylum options and extradition for political speech. The Hong Kong attorney sets Snowden up with Robert Tibbo, another human rights lawyer. Snowden is subsequently charged with three felonies back home. They discuss taking Snowden to Iceland or Venezuela. He winds up in Moscow, Russia and is permitted to stay for one year.

A rather interesting clip is when the international lawyer meets to discuss the three felony charges under the Espionage Act, a US domestic law from WWI to eliminate in-country spies. WWI propaganda under Woodrow Wilson had similar forms of political repression with “big lies” while stifling and challenging dissent. Snowden was being placed in this WWI context. He was not however, a spy, but a whistleblower.

Snowden begins to pack his things and organize his stuff. On his bed is copy of Cory Doctorow’s, Homeland. This is a quite apropos novel since it includes two afterword essays by computer security researcher and hacker Jacob Appelbaum, and the late computer programmer and Internet activist Aaron Swartz.

Near the end of the film, we learn that the FBI and the UK teamed up to find Snowden and that the UK Government ordered Guardian investigative reporter Ewen MacAskill to destroy all of his devices with content provided by Snowden. Apparently, the United States still has greater freedom of the press than the UK.

We also see the White House calling for Snowden to surrender and claim his due process rights before a court. President Obama does not think Snowden was a patriot; he thinks there was a “law-abiding” way for him to express concerns and dissent in “orderly” fashion.

We also see footage of Glenn Greenwald’s partner David Miranda being detained after a flight from Berlin to Heathrow. This was a clear jab at intimidation and reminder that national security is now gratuitous, far-reaching, intimidating to individual people and internationally orchestrated. It provides evidence of the NSA and GCHQ working in cahoots.

We are shown the “Dagger Complex” in Germany, a United States military base that tells of our collusion with Chancellor Merkel and our interest in running drone programs through Germany as cover. Additionally, reporter Jeremy Scahill is shown following up and investigating reports from a second anonymous whistle-blower. William Binney is also featured at the end of the film. The bookending of Binney is important for the film’s thesis. Snowden was not a disconnected isolated character. He wasn’t alone in wanting to come forward.

At the end of the film, Greenwald is in a hotel room with Snowden in Moscow. At this point, Greenwald must have believed Snowden’s fear that every conversation could be recorded. So Greenwald writes down names and facts in between generic phrases, like something from Mad Libs. He places everything on paper to show Snowden in the hotel room. In Moscow, Greenwald reveals to Snowden that the work of Jeremy Scahill (via another whistleblower) shows that the US was working with other nations and governments to collect data and use drone weaponry. For instance, drone strikes that were done through Germany were traced up to POTUS. Snowden was stunned to learn it. Then Greenwald reveals that “Citizen Five’s” (if you will) whistleblowing has helped the public to learn that POTUS has 1.2 million specific citizens on a watch list. Again, Snowden gasps.

Conclusion

Historian Lawrence Davidson has written of Edward Snowden:

“. . .Edward Snowden decided to release massive amounts of secret government data in order ‘to make their fellow citizens aware of what their government is doing in the dark.’ However, what the historical record suggests is that, under most circumstances, only a minority of the general population will care. Thus, in the case of the United States, the effectiveness of whistleblowers may be more successfully tested in the law courts wherein meaningful judgment can be rendered on the behavior of the other branches of government, than in the court of public opinion. However, this judicial arena is also problematic because it depends on the changing mix of politics and ideology of those sitting in judgment rather than any consistent adherence to principles. In 1971 judicial judgment went for Ellsberg. In 2013, men like Manning and Snowden [and Assange] probably do not have a snowball’s chance in hell.”

This astute observation is troubling yet reality-based. Snowden’s actions don’t seem to be admired by a majority of citizens and President Obama certainly knows this. Perhaps the film can help to relay more information to people and become more than just a political thriller. I think the film tried to emphasize the need for people to care about this issue. The results are yet to be seen. For Snowden and Greenwald and everyone else involved with this film, they had to act.

Snowden knew he had to act, gambled on his activism picking up speed, and needed to reveal classified information to make his statement. We know this because William Binney and Poitras, and a host of other reporters, producers, academics and activists, are continually marginalized and harassed at gun point.

In Rolling Stone, Greenwald had a traditional Voltaire-styled perspective on speech, “To me, it’s a heroic attribute to be so committed to a principle that you apply it … not when it protects people you like, but when it defends and protects people that you hate.”

A possible defense for President Obama is that he inherited a dog’s dinner from the Bush Administration in the way of American Foreign Policy. A recent argument by Aaron David Miller, an elite liberal propagandist, follows this trajectory. He was left to maintain or heighten all provisions and engaged in a dangerous, perhaps unlawful, search for Osama bin Laden on sovereign Pakistani soil. President Obama pledged to take boots off the ground and vowed to only apply “smart power” to conflict zones and flashpoints. He tried, and has succeeded, in making high tech protection a populist positon accepted by the mainstream electorate. This is not a compliment.

Some detractors of Snowden maintain there is an unsettling racialized component within this story. It is argued that since some President Obama antagonists are white, and not all applied the same level of work when Bush was President for eight years, their work is illegitimate or at least suspect. This to me is false. Snowden had Bush disenchantment and there is no question that Greenwald (How Would a Patriot Act?) and Poitras did as well.

President Obama doubled down on Bush’s surveillance policies and enhanced them dramatically in forming his strange interdependent political platform. The President relentlessly tries to suppress the image at home that his foreign policy is disliked by the world. This effort is the main reason for the surveillance and hence the whistleblowing. I will defend President Obama from the lily white Tea-Party and GOP at large, but that should be everyone’s limit.

In accord with Snowden skepticism, I have read Sean Wilentz’s disturbing tales of Snowden in the New Republic. He states that Snowden:

“. . . became furious about Obama’s domestic policies on a variety of fronts . . . he was offended by the . . . [new president’s] ban on assault weapons. [Snowden remarked,] ‘. . . I’m goddamned glad for the second amendment,’ Snowden wrote, in another chat. ‘Me and all my lunatic, gun-toting NRA compatriots would be on the steps of Congress before the C-SPAN feed finished.’ Snowden also condemned Obama’s economic policies as . . . a . . . scheme “to devalue the currency absolutely as fast as theoretically possible.” (He favored Ron Paul’s call for the United States to return to the gold standard.) In another chat-room exchange, Snowden debated the merits of Social Security.”

Wilentz writes that, “Snowden’s disgruntlement with Obama, in other words, was fueled by a deep disdain for progressive policies.” And just recently in reaction to the film, The New Republic continued its anti-Snowden barrage. We learn that this cannot be pure whistleblowing since Glenn Greenwald has had “conservative” views on immigration and even litigated in protection of white supremacist clients. The New Republic sees Snowden et al as makeshift progressives who haven’t earned their progressive stripes. Maybe there is a point here: Snowden’s own previous history of political activism was disproportionate to the act of leaking the essence of the NSA’s secrets. Even this is irrelevant though, in my view.

I tend to reject the defense of the President on the grounds of comparing him to Bush domestically. Even as the ACA and the ARRA are important signature President Obama achievements, the spying and reactionary positions on civil liberties are just far too extreme. The film conveys this well and that is what makes this movie excellent. Snowden states, “If all ends well, perhaps the demonstration that our methods work will embolden more to come forward.” So far he is correct and the film is quite popular. Snowden hoped that the work he did was just a tiny part in what would lead to the Internet Hydra Principle, where the erasure of one would only ensure that three more would pop up.

Lastly, allow me to reiterate that Snowden should not be judged personally. It is possible he had unsavory political views, but people do change and evolve. He is a young man. For those that consider Snowden correct in principle but illegal in practice, again consider that William Binney’s legal assertions and complaints were met with harassment and punishment.

Snowden and Greenwald have a unique political versatility. It seems at one point or another they have occupied and navigated the multiple realms of progressivism, libertarianism, and the moderate areas in between.

Ultimately, my final word is that Citizenfour was extremely well done. While it seems to irk liberals (aka non-progressives) that Snowden and Greenwald may be apolitical and amoral opportunists, I simply judge them by the merit of their conclusions, which are , in my view, heroic.

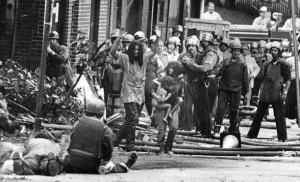

On Friday, September 20th 2013, the Full Frame Theatre in Durham, NC hosted the premiere of a film called Let the Fire Burn by filmmaker and director, Jason Osder. It was supposed to premiere during the Full Frame Film Festival in April, but had to postpone its Durham debut until Full Frame’s Third Friday Free Film Series. It was a documentary about the bombing of an organization called MOVE and historical developments concerning the group’s political repression by the city of Philadelphia since 1978. Osder’s premiere of Let The Fire Burn was absolutely riveting.

On Friday, September 20th 2013, the Full Frame Theatre in Durham, NC hosted the premiere of a film called Let the Fire Burn by filmmaker and director, Jason Osder. It was supposed to premiere during the Full Frame Film Festival in April, but had to postpone its Durham debut until Full Frame’s Third Friday Free Film Series. It was a documentary about the bombing of an organization called MOVE and historical developments concerning the group’s political repression by the city of Philadelphia since 1978. Osder’s premiere of Let The Fire Burn was absolutely riveting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.